By The Feminist Wire Associate Editors ![]()

We write in celebration of our visionary sister and comrade/comadre, Aishah Shahidah Simmons, black lesbian feminist, cultural worker, filmmaker, incest and rape survivor, and the creator of NO! The Rape Documentary (2006). This feature-length, internationally acclaimed, award-winning film, with Portuguese, French, and Spanish subtitles, a two-hour supplemental educational video, and an accompanying 100-page study guide (funded by the Ford Foundation and published in 2007), which includes national rape and sexual assault resources organized by state and a bibliographic treasure box of over 90 recommended readings – urges us to call rape out and end it. The latter she notes as a “non-negotiable necessity.”

We want to pause and acknowledge Simmons and this black feminist labor of love not only because she is a pioneer of the contemporary anti-violence movement, but because her work, which began in 1994, helps ground current moves to raise awareness about rape, sexual assault, and other forms of sexual and gender-based violence. More, Aishah Shahidah Simmons provides an opening to center and make present the continuum of too-often invisibilized feminist labors against rape, in which her work is deeply rooted and from which it emerges.

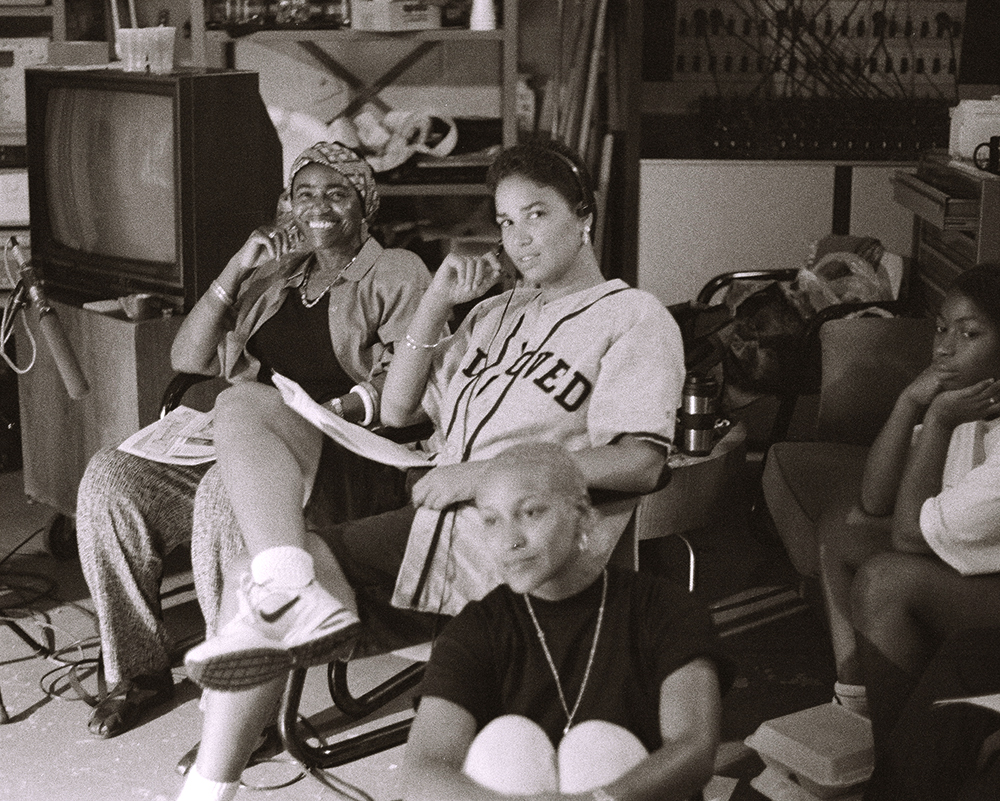

![]()

NO! Production Still: featured Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons, assistant director Nikki Harmon, set decorator Kia Steave-Dickerson_ associate producer /prod. manager Wadia Gardiner, Photographer ©1999

Recently, the #MeToo online movement has made space for women, some for the first time, to share their experiences of sexual harassment and violence. Initially, the hashtag was incorrectly deemed to originate with actress Alyssa Milano, who tweeted, “If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted write ‘me too’ as a reply to this tweet.” Milano’s tweet was a response to rape allegations against movie mogul Harvey Weinstein. However, #MeToo was in fact created a decade ago as “me too” (not an online campaign) by Tarana Burke, who is currently program director for Brooklyn-based Girls for Gender Equity. And though the current iteration of #MeToo exemplifies a significant historical social media moment, it began as a grassroots social movement, with the aim of empowering young women of color sexual assault survivors.

#MeToo, though initially focused on young women of color, seems in the current moment to have transcended race. This matters. It matters because women of color have been doing the work of “me too” for a very long time. And yet even proper attribution, though important, fails to offer adequate recognition of so many other women. In contemporary viral moments, we routinely fail to note the intricate layers, nuances, and intersections of these voices and works across several decades of anti-rape activism. It also matters that Milano is an Italian American Hollywood actress, best known for television shows like Who’s the Boss?, Melrose Place, and Charmed. It matters that she is an actress/activist who happens to have the ear not only of Hollywood but many Americans. Milano’s tweet calls rape culture back to consciousness in a very particular time in history, against a very famous white man – with very famous and mostly white survivors – and within the context of a “pussy grabbing” white nationalist hetero-patriarchal misogynist capitalist trans-antagonistic POTUS. The wide-ranging and fiery response to Milano’s tweet may very well be a covert way of saying #HimToo.

In short, Milano’s tweet likely caught on as it did not because critiques of rape culture are novel, but because hashtag activism makes anti-violence resistance accessible, easy to grasp, and contagious, and because who tweets about what, how we imagine the survivors, and who we visualize the perpetrator/s to be, matters. Still, online activism, with its tendency to strike quickly and then fade in response to moments such as this, is often ignorant of its historical precursors. Grounding viral moments in their historical, theoretical, and movement-based genealogies is critical, both to name the labor that made the moment possible and to ensure that discussions and actions continue beyond the Internet.

To be sure, online and hashtag activism may generate benefits, including providing discursive space. A great example is the Black Lives Matter network, which was first introduced to many of us as a hashtag. Notwithstanding BLM’s successes, some of the challenges of online and hashtag activism more broadly are that it erases herstories, movements, complexities, and laborers. As Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor argues, #BlackLivesMatter developed out of longer and continuing movements of and for Black liberation. So too do contemporary incarnations of the anti-rape movement.

#MeToo was not created in a vacuum. It is not a single story. And its focus is not limited to rich white cis men who victimize. The anti-rape movement is about the eradication of heteropatriarchal white supremacy writ large and its specific manifestations of sexual, gender, and racial violence. And if we look at the contributions of radical diverse women who have been fighting against rape culture for two centuries, we see the herstories of sexual violence across inter-racial, intra-racial, and intra-communal lines. It’s easy to critique white supremacy and white feminists for erasures and white men for rape. It’s more difficult to provide complex and winding history that forces us to broaden the map of violences and resistances, and engage intra-communally and historically.

![]()

Aishah Shahidah Simmons, Toni Cade Bambara, & Kim Hinckson, 1994 courtesy: ©

It is not lost on us how the works of first-, second-, and third-wave black and of color feminists have been left out of the current discourse, or how Burke’s initial focus on young women of color and intra-racial rape in communities of color has been excised. Rape culture impacts all women. But what cannot be ignored is how the emphasis on “all women,” particularly in hashtag activism culture, tends to decenter black women and women of color, and how each have herstories of intersecting oppressions and violences that are overwhelmingly increased because of race, ethnicity, and gender reinforcing each other. Further, some women’s narratives of sexual violence have historically been disbelieved, and are still suspect now.

In fact, as Kimberlé Crenshaw argued in 1989, sex discrimination laws were put in place to protect white female sexuality/chastity (from black men), not to protect black women. Yet sexual violence was often the pretext for terrorizing black communities. She posits, “sexist expectations of chastity and racist assumptions of sexual promiscuity combined to create a distinct set of issues confronting black women.” That is, gender makes black women and girls susceptible to sex domination and violence, while blackness denies them state or local protection. Crenshaw notes that some courts went as far as to instruct juries that black women were not to be presumed chaste, leaving them to fend for themselves. Of course, the erasure of some survivors over others is nothing new. Similarly, the blotting out of black and of color anti-rape activists is not innocuous.

![]()

NO! Production Still: featured interviewee Barbara Smith and producer/director Aishah Shahidah Simmons)_Joan Brannon, photographer ©1999

We understand anti-rape activism as the resistance to sexual coercion in daily practice and its institutionalized forms. Because rape, as Angela Y. Davis argued in 1978, is the social relations of capitalism and a capitalist interstate system infused with patriarchy and racism, its existence is historic, intentional, and pervasive. Historically, anti-rape activism is present in the contexts of state-sanctioned sexual, gender, and racial violence during colonial and imperial conquests and acts of war; within institutions such as slavery, marriage, prison, health care, immigration, and education; and in the daily acts of our socio-economic and political interpersonal relationships. Anti-rape activism is fueled by and exists alongside sexual violence, be it within survivors alone, or in collectivity with others who strategize against harm. The politicization of our contemporary anti-rape movement is grounded in the global histories of decolonization and Third World Liberation, anti-slavery and abolitionary struggles, and U.S. anti-war, Black Power, civil and labor rights, Indigenous sovereignty, and feminist movements.

The 1960s and 1970s are central to historic understanding of U.S. anti-rape activism, particularly in its institutional formations. The anti-violence work of these decades was deeply informed by Indigenous and Black women’s activism against white supremacist sexual coercion and exploitation that extends back into U.S. settler colonialism and slavery. These efforts developed hand in hand with women’s liberation movements toward greater economic, reproductive, sexual, and cultural autonomy. Anti-rape activism became entangled with other movements, including white middle-class women’s economic empowerment, in ways that made some pathways possible for these women while closing off opportunities for women of color and poor women.

![]()

NO! Production Still: producer/director Aishah Shahidah Simmons and featured interviewee Johnnetta Betsch Cole _Joan Brannon, Photographer ©1999

Anti-rape activists for decades have worked, together and sometimes apart, to raise awareness of sexual violence and to strategize against it. Interventions have targeted “private” lives and political institutions, while at the same time challenging the divide between public and private. The Combahee River Collective, Flo Kennedy, June Jordan, This Bridge Called My Back, and many other anti-racist efforts pushed to account for the whiteness of the 1960s-1970s anti-rape movement, grounding the work in a more expansive understanding of slavery, settler colonialism, and imperialism that targets Black, Indigenous, Third World, women of color, and queer and gender non-conforming bodies. The movement was refigured again by the spread of neoliberalism and inclusion of anti-rape efforts inside institutions via Title IX and sexual harassment law, moves that reframed anti-rape as largely a middle-class white women’s concern. How, scholars and activists have asked, can the movement remain radical when funded by the State?

![]()

Aishah Shahidah Simmons and Black feminist scholar-activist Beverly Guy-Sheftall at the National Black Arts Festival in Atlanta, Georgia_Michael Simmons, photographer ©1996

NO! The Rape Documentary (and its supplemental materials), as it explores the transnational operations, reality, and effects of rape, sexual assault, and other forms of violence committed against women and girls, and as it deploys first-person testimony, spirituality, activism, and the academic and cultural works of Black folk, is a continuation of historical work, particularly the intersectional lessons of Black feminists who laid the groundwork for anti-rape activism in Black and other communities. Simmons’s cinematically groundbreaking work is significant because it forces us to think about rape through BLACK women’s experiences and intra-communally. That is, it pushes us to call out and resist not only the Weinsteins in every industry but the Bill Cosbys and R. Kellys, too. It refuses invisibility, marginalization and/or tokenism and demands a social, political, cultural, ideological, structural, institutional, and interpersonal shift.

Earlier this year, Simmons gave a powerful presentation to students of all genders and sexualities at King-Drew Magnet High School in South Los Angeles, a predominantly Black and Latinx campus. Simmons’ presentation was followed by student-led workshops on sexual violence, harassment, and rape culture conducted by youth from the Women’s Leadership Project. Simmons’ statements on the connection between white supremacist hetero-normative violence and racialized sexual terrorism against girls of color resonated strongly with WLP students. Twelfth grade student Drea Wooden noted that normalized sexual violence against Black girls and girls of color is seldom discussed on most school campuses. Tenth grader Cheyanne Mclaren stressed that Simmons’ talk reaffirmed that “sexual violence is an important issue for communities of color because women of color are seen as lesser in value than white women and women of color aren’t getting the justice they deserve.”

![]()

WLP students, peer educator Issachar Curbeon, Aishah S. Simmons & TFW’s Sikivu Hutchinson

![]()

![]()

We are celebrating Simmons because her work marks a pivotal moment in anti-rape activism. Because NO! “let’s you know what you need to know fast” (“Because We”), and has inspired new generations of womanists and feminists to resist and take action against a global regime of sexual violence. Because she reminds us that all oppressions are linked. Because she holds us accountable to how we respond to sexual violence. Because she charts an Afro-futurist path for collectively doing things differently and imagining and realizing communities free of rape, assault, and incest. Because this work was created in community for community. Because NO! centers and hopes to heal black and brown sacred flesh. Because Simmons has shown up for us and for survivors everywhere. Because when and where she enters, she brings all the anti-rape feminist and womanist foremothers, co-laborers, and survivors with her. Because Aishah Shahidah Simmons taught us that NO! is a complete sentence that not only explicitly names rape, which may sometimes be cause for erasure because language is political, but unequivocally refuses it and calls us and our communities to action.

The post Recovered Histories of Anti-Rape Activism: Celebrating Aishah Shahidah Simmons and Intersectional Approaches appeared first on The Feminist Wire.